sketching tutorial

Tuesday, October 28, 2014 at 03:54PM

Tuesday, October 28, 2014 at 03:54PM

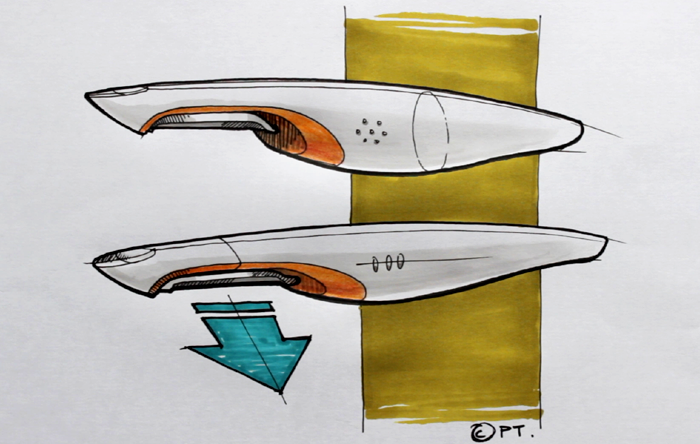

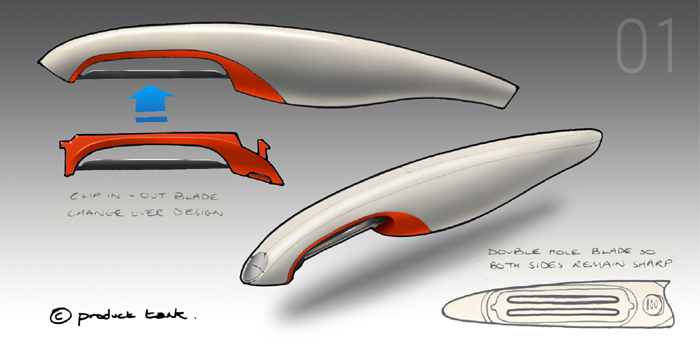

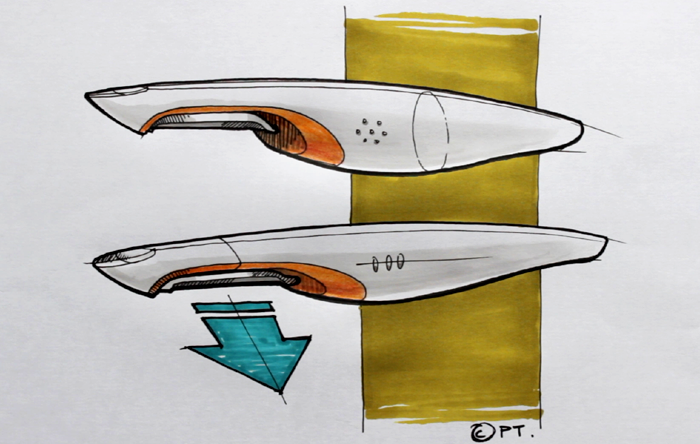

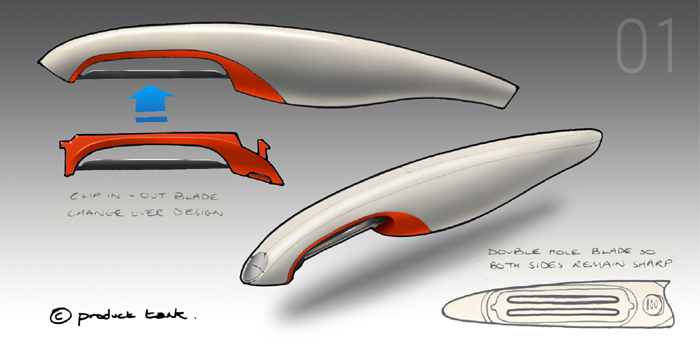

I have completed a video tutorial on product design sketching and rendering by hand and photoshop.

If you want to watch the video, click - here

Watch all my videos on Product Tank TV

Watch all my videos on Product Tank TV

A product design blog containing unique observations, advice and ideas to improve objects from the mind of Product Tank.

You can subscribe to receive my future blog posts by email, each time I publish new content - just click on the orange RSS symbol (on the right) and you will be taken to feedburner.

You can subscribe to receive my future blog posts by email, each time I publish new content - just click on the orange RSS symbol (on the right) and you will be taken to feedburner.

Tuesday, October 28, 2014 at 03:54PM

Tuesday, October 28, 2014 at 03:54PM

I have completed a video tutorial on product design sketching and rendering by hand and photoshop.

If you want to watch the video, click - here

Monday, December 16, 2013 at 03:08PM

Monday, December 16, 2013 at 03:08PM I see lots of student work which looks amazing, but I know cannot be manufactured. The problem is a lack of time or care, where the designer has not made a model to test their idea (maybe a model is not part of the grade criteria). I want to address this, because I am noticing this trend increasing. So I thought about making an instructional video for students. Then I heard the Baz Luhrmann sunscreen song and wanted to use it as the inspiration and the idea went from there. Please watch the video.

The narration:

> Students of product design - make models.

> I have seen hundreds of portfolios, where students have been too quick to use CAD without first testing their ideas to see if they will work.

> The long term benefits of making models to quickly identify and solve problems has been proven by product designers over and over again. The rest of my advice is purely opinion. I will deliver this advice with a large nod to Baz Luhrmann, now.

> Design is a journey, when you begin a project you should not know what the end destination looks like. Do not be in a rush to get to the final solution. Get lost, go down many paths and enjoy what you discover.

> Always go too far and then come back.

> Research, know your audience, walk a mile in their shoes and if you can't, try to understand all the nuances surrounding who you are designing for and what you are designing.

> Never stop asking why.

> What ever you design, always try to make it new in some way.

> The brief is king, challenge it, exceed it, but you must answer it.

> CAD is only one tool, currently it cannot tell you how something feels or behaves in your hand or how heavy or uncomfortable it is in use.

> A pretty picture of a design is not a product.

> Take things apart, you cannot hope to improve anything if you don't know how it works.

> If you take a found object and put a light bulb in it, you are just up-cycling.

> People say you are only as good as your last project, rubbish! You are only as good as your next project because of everything you have learnt. Make lots of mistakes and learn from them.

> No real good has come from forcing anything, take regular breaks. Never think, 'that will do'.

> Don't design to make money, design because you care and trust me about making models.

make models,

make models,  video in

video in  model making,

model making,  product design advice

product design advice  Thursday, November 7, 2013 at 03:42PM

Thursday, November 7, 2013 at 03:42PM

Lots of people assume they need a lot of equipment when model making, but actually you can get by with very little equipment (good power tools are a great help). When I was in university there was a fantastic spray booth with water wall, turn table and fan system. But despite the fact that it was a joy to use, the spray results that I acheived are no different to my current high tech system, which is newspaper, two strips of wood to counter wind and an empty bit of space. A few things to consider though...Try not to spray below about 8 degrees C and ideally spray over 10 degrees C. Make sure humidity is as low as possible and what you are spraying is dry and even though outdoors, always wear a mask and work out wind direction before you spray to avoid accidents!

Monday, August 26, 2013 at 03:56PM

Monday, August 26, 2013 at 03:56PM I always use a mental checklist that I run through on each design project, but since the car, I have decided to create and use a written one to go over during and just before the release of each project. This is my initial list, that I will refine as time goes on. Every project can be developed a little further and it's not until I have released a project and been given feedback that I can come up with new ways to improve, but this list is to help get each project as far as I can first. Hopefully it will help you too.

Beginning:

Have I come up with a brief or idea for a solution to a problem that doesn't exist?

Have I done enough research?

Is this a concept for the sake of it?

Can the problem be solved another way?

Solutions:

Does the design idea address the need/problem sufficiently?

Has it been designed not just engineered?

Have I pushed the design far enough?

Am I churning out the same things as everyone else? Or is it being different for difference sake?

Is the detailing good or refined enough for each individual area on the concept?

Is there a balance between simple and complex areas?

Have the materials been properly considered?

Can it be engineered to be more environmentally friendly? (this will require a sub checklist)

Have textures, colours and finishes been properly considered and pushed far enough?

Packaging where applicable?

Does the solution provide real benefit?

Is it too gimmicky - Does it have a very low gimmick rating?

Is it innovative in its size to complexity ratio.

Have I made everything thin enough, light enough, have I pushed the materials to their limits.

Publishing/presentation

Does it look cool in the images, is the quality as high as I can get it?

Does the presentation tell the story to someone not familiar with the project?

check list,

check list,  checklist in

checklist in  process,

process,  product design advice

product design advice  Thursday, June 27, 2013 at 02:30PM

Thursday, June 27, 2013 at 02:30PM

I was recently very derogatory about the latest Electrolux design lab finalists who submit blue sky design concepts under themed categories. The concepts selected this year do not seem to be as strong as previous years. I cannot understand why they were presented (without a reality check from tutors and peers prior to submission) and why the judges decided that they should be selected. This is not me trying to knock student work, I only want to support students, but I believe you never learn as much from positive comments as you will from constrictive criticism.

For this years competition, Students could submit work under three categories, one of which was air purification. I do not wish to single anyone out as I think they were all bad, but as an example, no matter how far into the future you go, I cannot see how an air purifier the size of a match box worn on the wrist outdoors, can work. Just mathematically, anything that small could not shift the volume of air necessary to improve air quality in an outside environment effected by wind especially when you factor in the distance it will normally be from your face.

advice,

advice,  blue sky,

blue sky,  competitions,

competitions,  electrolux in

electrolux in  product design advice

product design advice  Sunday, June 23, 2013 at 03:44PM

Sunday, June 23, 2013 at 03:44PM

Tuesday, June 11, 2013 at 02:22PM

Tuesday, June 11, 2013 at 02:22PM

A while ago I responded to a series of questions about my design process with Maren Fiorelli,

a design student at Columbia College, a slightly edited version of some of my responses is here:

1. What is the first thing you think about when beginning a project?

Once I have identified something I’d like to tackle – a product that I think I can improve on or an area that needs improving, I research to see if this hasn’t already been done, as something better may already exist, but it just hasn’t become mainstream enough to hit my radar and there are few things worse than spending lots of time on something only to have someone tell you that they saw the same design idea or product 4 years ago.

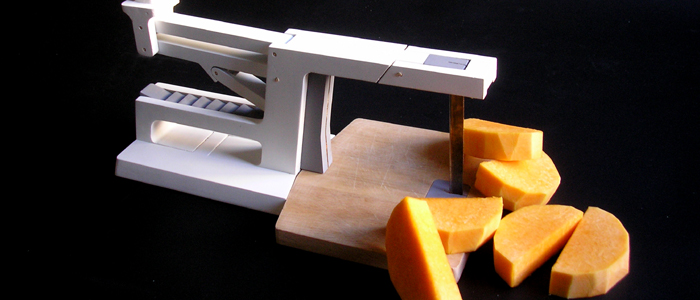

As an example, my Nan struggles to chop vegetables because of weak wrists, as a designer, should I design a better chopping gadget, or order packets of pre-chopped vegetables from the supermarket? There is always another way around a problem, sometimes this is an advantage as it allows you to break away from the norm, other times it is a disadvantage as it means the problem doesn’t really exist. So I have to carefully consider if something is worth tackling as it’s quite an investment of time. I don’t get it right every time either and I do come up with a lot of dead ends. As the image in this post and this video demonstrates:

2. What are some key elements that you try to emphasize in your products?

It’s all about functionality. I have my own design style, but looks are not really important to me, which is weird coming from a product designer as of course I don’t want it to look butt ugly, but one man’s duck is another man’s swan – aesthetics are down to individual taste. If I had to choose between sacrificing looks or functionality, looks would get the chop every time – although I do think the role of the product designer is to balance both. What I am really looking for is an elegant solution, the solution which performs best in the most economical/simple way in terms of materials, functionality etc. It’s hard to describe but you know it when you see it. I will also always try to first solve the problem without using any (electronic) technology as I feel it’s always the most obvious path, too often designers will just stick a motor in something or a bunch of electronics.

For example, recently my mother was moaning because the battery had died in her electronic weighing scales, so she had to go back to her mechanical ones – they work perfectly and will continue to do so long after the battery in the electronic ones has died – if electronics provide a tangible benefit, then they should be included, but often I feel it’s an example of laziness on the part of the designer/marketing department and a needless use of resources to try and get a sale from a public that have been tricked into thinking they need something new – new is not necessarily better.

3. How do you create your master check list for these key elements?

I always create a list of things that I’d like to include, there’s the ‘nice to haves’ and the ‘must be able to do’s’. I (sort of) imagine everything it would be good to have, even if they may be currently impossible, but I think through as many scenarios as I can. Some ideas I put back on the shelf for next time, but all the things that will make the object better, I try to keep. It’s difficult to put into words quite how it works, but I try to include as much common sense as possible.

I also use a rule of thumb for the size of product I’m designing to try and include as many innovations/USP’s (unique selling points) as possible. If what I’m designing is simple (1 part) like a bread board, I’m looking for at least 1 USP. If it’s a complex product then I’m trying to find at least 7 USP’s to make it stand out. These USP’s should not be bolt-ons, so the thing looks like an extra out of the transformers movies, but must be incorporated into the design to add to the functionality as I believe there is no point in being different just for the sake of it when you can be different to the benefit of the product and the consumer.

4. What do you feel about universal design in relation to products for someone with a disability?

There are certain disabilities that require unique and adapted designs tailor made to the individual. What I like most about the principles of universal design is that by making an object as easy as possible to use for the people who would find it the hardest, you improve it for everyone, which has to be a good thing. If everyone is using the same equipment, then it’s one less barrier to being disabled.

5. I see that function is the most important aspect in your designs. How important is it to you to stay within the social norm for products that you create?

There are no revolutions in product design; everything is an evolution on what has gone before. I want my designs to be easily understood and used. I do not want to design objects that require massive instruction manuals. So to a certain extent I am designing things that I hope look familiar, but maybe have an element of surprize, like my pepper mill who’s lid turns into a funnel. I am not looking for people to buy or use my product designs because they are by me (otherwise I would show my face on my site etc which I never do), I would like what I create to be invisible, which means, I want my products to work so well that people don’t notice them. The majority of products function to complete a task – I use a can-opener to open a tin of beans, not because I love opening tins, but because I am hungry. When the can opener doesn’t work I get frustrated, because it becomes a barrier to achieving my goal. I never want my designs to be barriers. All products follow some form of social norm, they are styled for which-ever culture will most appeal to the consumer, which is why so many versions of a product exists. Even something as mundane as a toaster comes in many forms and colours to fit with the styling of your home.

6. What direction do you think that designers tend to overlook when they are designing products?

Mainly I would surmise that most mistakes that are made are caused by aggressive time constraints. Time is money, so there can be extreme pressure to hit a deadline.

I have direct experience of this. I once designed a garlic crush as part of a range of kitchen utensils. I made a solid Bluefoam model that was then realised in CAD and a rapid prototyping model sent back. I, the client and the rest of the office had a look at it and everything seemed ok, but no one tried to crush garlic with it as we would have broken the part. We pushed on with tooling, but on receiving the first off tool samples, I discovered (to my horror) that when crushing garlic the two handles just slightly pinched the skin in people’s hands when fully closed. Changing the tool was costly and no one was very happy, but due to aggressive timescales it was a mistake that no one spotted. I learnt a lot that week;-)

Product tank,

Product tank,  QandA,

QandA,  advice,

advice,  product design in

product design in  process,

process,  product design advice

product design advice  Tuesday, May 28, 2013 at 04:02PM

Tuesday, May 28, 2013 at 04:02PM

Back in 2012, I was getting emails from people asking where they could buy the New Rule concept ruler I had designed to help people with visual impairments. Enquirers wanted to buy them for their children to use in school and to help with exams when questions asked to measure an object on the exam paper in millimetres. I’ll be the first to admit that I have the business nouse of a dead mouse, so I contacted Ashley Sandeman, because he’s family, is very business minded (he’s written a book on it and has a rather interesting blog) and was thinking of starting up a new business. In the end we didn’t take the product to market, so I asked Ashley to write this article to explain why. I think this is an excellent example of how to determine the potential market size for a product you have designed before going to kickstarter etc. The design and enquiries happened before kickstarter was available in the UK, but there are valuable lessons here for anyone thinking of trying to take an idea to market with a loan, an angel investor, or through a crowd funding platform.

How you determine the “potential market size” when designing a product? A 5-step approach

Ashley Sandeman:

Step 1 – What do you honestly want?

It’s important before you start anything that you know what you want out of it and are honest with yourself.

I was looking for a business I could start, which would support me financially and allow me to launch other products leading to the full time employment of two people. For the sake of argument, let’s say I wanted a £50,000 turnover in the first year.

Knowing what I wanted and being clear about this lead to a series of questions:

All of these questions are important to answer, but I chose to focus on the potential market size to quickly highlight any problems.

Step 2 – Determining the potential size of the current market

First the quick way - via a keyword search. I used this because search engine data is aggregated. I tried several terms, but as an example, I used the phrase “ruler for visually impaired.” You can use tools such as Market Samurai to interrogate this data using keywords that reveal daily broad matches, phrase matches, and exact matches (which are best) for your words. It will also reveal the amount of competition for those words and the number of pages referencing your words. The Market Samurai data revealed that not only were very few people searching for “ruler for visually impaired,” but (at the time of writing) only 9 pages globally used the same phrase. There’s nothing wrong with a micro-niche. There’s a lot wrong with a market that hardly exists.

Now the long route, finding data on market size. This route will help explain why you see the results from the keyword research. I Google searched visual impairment sites until I could find data on visual impairment in school children. Not only had the contacts Product Tank received from people referred to school children, but He and I also felt this was the best group to approach. When we considered professions that used measurement there was always a better/more accurate alternative to the product. For example, engineers use computer models, digital callipers etc.

From a 2008 NHS (National Health Service) paper I found, the majority of people registered visually impaired in the UK are over 65. Under 18s make up just 4% of the group. Assuming 5-17 year olds would really benefit from the product, of those registered approximately 30% have an additional disability be it physical (most common), mental illness, a learning disability, etc. Looking at the available research I had to assume from a risk perspective that those with an additional disability would never take up the product.

Admittedly the data was not perfect, but it gave me a UK market size of 4986 potential customers.

In short, the market was looking quite small. I quickly generated a table in Excel using the data I’d gathered. Even if I priced the product highly at £9.99 (a large sum for a ruler) I’d need 100% uptake of the market to get close to my target £50,000 of sales turnover (4986 people x £9.99 = £49,858).

The figure of £49,858, minus expenses would be my profit and my expenses need to account for many things including tooling, manufacturing, CAD, prototyping, fulfilment, storage, accountancy, patents, licences, and wages factored into the process. In short, the UK market isn’t large enough to support the business - I needed a larger market.

So using the same techniques I then researched the US and found statistical information that indicated that just 1% of the US market is the same size as 77% of the UK market. I assumed a similar level of additional disability would occur in the US, but even so this gave a potential market of 383,000 people and I hadn’t yet considered Europe or Asia.

As you can see from my US Excel table, I only had to sell 11,495 units, just 3% of the market at $4.68 to get close to the same target I had in the UK. Looking purely at market size, things now looked more viable. The trouble is they weren’t.

I was beginning to determine the product’s price based on a figure I felt I needed to hit. Price should be based on the value you’re delivering, not on a figure you want to be paid. That I was leaning towards the latter was an early warning. I didn’t know the likely uptake of the product, but my search engine research (Market Samurai) had given me an indication. Despite the market size, people weren’t actively searching for the product in high numbers. Could it be that many didn’t feel it was a problem that needed solving?

Step 3 - Potential for Growth

As discussed, my research showed that new visual impairment cases make up a tiny percentage of the overall visual impairment figures. Age is a more likely determinant of poor visual health, and that wasn’t going to be my market. So after filling the market with a hopefully brilliant product on day one, once I’d reached a peak of initial uptake, the research showed that sales would be in decline from that point onwards. I know I’m making a lot of assumptions, but this is about getting a good feeling from a morning of research and making a decision to continue or not. The danger would be that I would always be running the risk of holding either more inventory than I could shift or running production so small I’d have to sell at too high a price.

There are a number of weaknesses with such a brief look at the market. Even people with good eyesight find reading a millimetre ruler difficult. Those children whose eyesight was fine, but who also found reading a millimetre ruler awkward may want to take up the product. There could be a larger market out there than I first thought. However, there’s a valuable business lesson here too: It’s easier to sell to an established crowded market than to a new market that doesn’t yet exist. Creating a new market is very expensive, and I felt at risk of doing that here. At least in a crowded market you know there are customers willing to part with their money. Could my market simply be anyone who needs to use a ruler, and my solution to supply them with the best ruler in that market? The answer here in my view is no. Rulers with large numbers are available. So are normal rulers and digital callipers. I’d be taking on the entire market with a product most consumers didn’t really need at a significant increase in price to a standard ruler (because of the extra parts), without the accuracy of a digital calliper.

Step 4 -, Understand your market, risks and competition

In understanding the UK and US markets my research showed that their education systems have different requirements. If you don’t understand your customer base you can’t help provide them with value. The first issue I faced was the metric system. In the UK we use centimetres and millimetres. In the US inches are a more common measurement. An inch is a larger measurement, creating a lesser visual impairment problem. It also creates a design problem as I can’t sell an identical product in both countries. This is before I even mention marketing and distributing in the US. The entire venture would require a lot of viral support from the visually impaired network as I couldn’t hope to cover the country.

Finally I examined the school system. Again if you Google something for long enough, or speak to the right people you’ll find your answer. Research can be a pain, but nothing compared to the pain of losing time and money. The UK school system did not penalise children for being unable to answer a measurement exam question, and such children could be provided with a modified exam paper if requested. The parents querying the availability through Product Tanks website might not be aware that their children didn’t need it for an exam, and so potentially are not customers. As for the rest of the world, as my keyword analysis revealed, people did not appear to find it a large enough problem to search for a solution.

Step 5 – Finally, (and most importantly) be honest

After all this I concluded that it was unlikely I would get a return on my investment of time and money. Helping the visually impaired is a great cause, and the knowledge that the product would be helping people was a clear motivator to bring it to market. But it would need to be approached from the perspective of philanthropy, not business. As hard as that sounds I think you need to be invested in this sort of market for the love of the product, and the risks of losing a lot of money was too great for me to adopt it for solely business reasons. If you’re going to live and breathe your business, you have to love it.

Ashley Sandeman is a business consultant and author of “101 Things I should have been taught at business school.” You can find his blog here

Wednesday, May 22, 2013 at 05:09PM

Wednesday, May 22, 2013 at 05:09PM

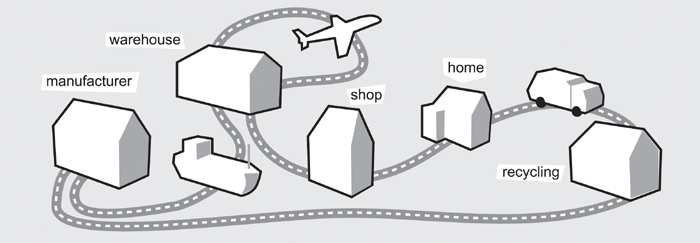

When I am designing a product I often only focus on the products relationship with the end user, without realising all the other areas where I can innovate. Products are manufactured, stored, delivered to warehouses, shipped in containers, displayed on shelves, taken home, used and kept in cupboards, cleaned etc. The life of a product does not begin when the customer opens the packaging. If I can save weight, materials, number of parts, size (flat pack), storage, ease of part replacement, ease of dis-assembly, then I am making huge cost savings and environmental savings, etc. There are loads of areas within product design where a designer can make a huge difference, a long time before it has reached the end user and a long time after and all too often I think this is overlooked.

Monday, May 20, 2013 at 02:42PM

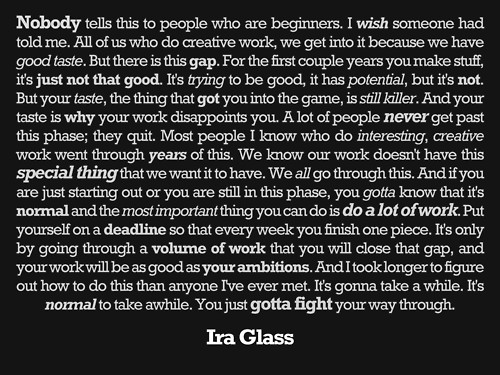

Monday, May 20, 2013 at 02:42PM It is very rare that I will post anything on this product design blog that I have not designed, thought or written myself, but every so often I see something that I instantly know, no matter how much time, effort or skill I put in, I will not be able to better. Quite a few years ago, I saw the quote below and thought at the time how well it encapsulated my own journey. Then recently whilst trawling the web, it resurfaced again and was a timely reminder for me about perserverance.

Ira Glass in

Ira Glass in  product design advice

product design advice  Tuesday, May 14, 2013 at 03:23PM

Tuesday, May 14, 2013 at 03:23PM

The uncle of a friend of mine came up with an idea for a product; what the product was is not important, suffice to say, it was an idea so commercially bad, it was the chocolate tea pot of bad ideas. He wanted to take the design to market and with no product design experience, conducted a brief internet search and found an experienced Product Design company offering design evaluation services. From the website they had all the right bells and whistles and offered to evaluate the design free of charge. He went along to meet them and they reviewed his idea and surprisingly told him it had legs. The next step would be for their patent team of highly experienced patent experts to do a search to check if the idea had not already been patented. My friends uncle, parted with the cash (a princely sum) to allow the initial search to be conducted. The fee seemed steep, but they assured him that there would be a lot of hand holding along the way and their experts were, well… experts. Unsurprisingly, the initial search came back with articles of a similar nature, but nothing that was close to his idea (with good reason, his idea was a howler). For the next stage, the company would prepare various sketches to get rough tooling quotes and patent his idea. The fees were starting to increase, so my friend heard about his uncles’ folly and put him into contact with me. A few quick questions were enough. I felt like Simon Cowell on X-Factor. ‘Haven’t any of your friends or family told you, you can’t sing?’

‘No, they all say I have a beautiful voice’

It didn’t feel good.

'What do your friends and family think of your idea? Have you made a rough model to see if your idea will work?' I asked, he replied he hadn’t made a model, he had never done any of this before and didn’t really have any DIY skills. He also hadn’t told many people because he was worried about giving his idea away, but his wife thought he had a good idea, because she had experienced the problem. The idea was a classic combination of two products that worked spectacularly well at the jobs they were intended for separately and would work spectacularly badly when forced together to make a new multi-purpose object. ‘Go and buy these two items from a hardware store, cut a hole in one and stick the other through it, add a bit of gaffer tape and then go for a walk and try to use it,’ I advised – see what problems this creates and think around how to solve those problems. He did so and realised that he was potentially being taken for a ride.

Every design consultancy has mouths to feed and there are a lot of people out there with money who are having bad ideas, so sometimes paths may cross. I’m not condoning this, but there were faults on both sides. The consultancy should have told him that the idea needed radical development or scrapping and addressing the problem in another way, before taking a fee for a patent search. Also a few hours on the internet and in the shed would have solved many of his problems and highlighted many new ones. With a lot of work the design company may have been able to completely change the idea to create a half decent design, but would it ever be marketable and would my friends uncle have enough to invest to not only get it to market, but also market it so that people would invest or buy it, I don’t think so. With all my experience I could not see a way of making it work. My friends uncle had identified a problem, it was just the way he went about analyzing and solving it. You don’t have to be a designer or inventor to come up with good ideas, but there are a few things you have to do to test if they are any good.

Once you have identified the problem, you have to ask yourself does the problem really exist? Has it been solved in another way? In the space race, America spent 2 million dollars designing a ball point pen that would write in a zero gravity environment and the Russians just took a pencil (research suggest that this example maybe a myth but it does nicely illustrate a point). If indeed you have found a problem without a satisfactory solution, then you have to research to see if it hasn’t already been done and you are just not aware of it (the internet is great for this). Then, you don’t need to be good at sketching or making models, but I cannot stress enough, you do need to make rough, quick models to find the faults with your idea. Use card board, plasticine, even salt dough – anything you can get your hands on and test your ideas on family and friends before approaching a designer – whatever it takes to avoid that chocolate tea pot. I'm going to blog around this a lot more in the future.

advice,

advice,  process,

process,  product design in

product design in  process,

process,  product design advice

product design advice  Friday, April 5, 2013 at 02:28PM

Friday, April 5, 2013 at 02:28PM Anyone who thinks you are only as good as your last design project is misguided – I hear this said all the time, but the fact is, you are only as good as your next product design, because you hopefully take forward all the things you have learnt from your last. Whilst it is important to make the lastest completed project as good as possible as this will be the most recent thing you can be judged on, I also think it is very important to be able to make mistakes and show how you have progressed. Having had quite a few product design projects in my past where the outcome, on reflection, has not been as strong as I would have liked, I now know not to be dishartened, just to analyze where to improve and come back stronger

lesson,

lesson,  product design,

product design,  questions,

questions,  thoughts in

thoughts in  process,

process,  product design advice

product design advice